Discussion – What is Estonian art and who does it?

9.11.2021

Sulje

Sulje

9.11.2021

Marika Agu, curator and archive project manager at the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art, discusses about Estonian art with artists Alexei Gordin, Flo Kasearu, Camille Laurelli, Liina Pääsuke, Bita Razavi and Steve Vanoni.

Marika: My intention in this discussion is to talk about abstract entity as Estonian art and also on a larger scale how is it to work in the Estonian art scene? Thinking of national pavilions in the context of Venice Biennale, the precondition to exhibit there is not necessarily the nationality of specific country but rather the work on local art field. Therefor I ask what kind of art and which artists represent a country? You are all very talented artists, working simultaneously in several countries and have international presence. Does describing artists by their nationality actually makes sense? With which place do you identify yourself with? Which context do you belong to?

Steve: I had no choice being born in California. Although I think that art transcends nationality. I really don’t care about borders. I’m interested in art and great work. Here in Estonia are some artists, whose work you see as obviously related to the country, their roots, and I love that as well. Work that is national has a very particular flavour to it.

Alexei: When I wake up in the morning, I don’t think about what national context I am in. It’s not our choice where we are born. I just want to make art and bring my ideas to life.

For me it has gone quite well, because being Russian-Estonian brings an interesting aspect to my work, although it’s not my choice. Generally, nationality is not something that defines my practice.

Marika: Is nationality like a ghost that haunts you, or like a marker for people to recognise you?

Alexei: If you meet new people in an international context, then the first question is where are you from?

Marika: Liina, where are you from?

Liina: Väätsa.

Steve, Alexei: What, where?

Liina: Väätsa is a little village in the middle of Estonia.

Marika: You don’t say that you are from Vienna?

Liina: No. I think a lot about being Estonian. Recently, my practice has become more textual, I’ve started to work more with language, and therefore the question of Estonian language or being Estonian comes up immediately. If I choose to make work only in that language, it excludes a lot of people, and then the question of nationality comes up.

Liina Pääsuke, still from graduation project "Nancy Nakamura’s Rap Unit", 2021

Marika: Flo, what is your experience when exhibiting at large scale art events, such as Gwanju Biennale, Survival Kit, or Frieze London?

Flo: In my experience, when exhibiting abroad, Estonia is not a sexy place to reference in the art world, as perhaps was more the case in the 1990s after the Soviet Union collapsed. Having this EE in brackets behind my name is quite basic compared to artists nowadays who even have not two but three countries listed as their origin.

Flo Kasearu at Frieze London art fair, represented by Temnikova & Kasela gallery, 2021. Photo: Theo Christelis

Marika: How to measure success for an artist? Is it international exposure?

Alexei: Success cannot be defined – is it recognition or the income? In the art field it tends to be more complicated – often you can’t have both. What is success then?

Liina: I have a third way of measuring success. I get that money is important, because it changes the way I deal with things, but my work is not so much related to the fact that my name is known or how much money comes in. I still have naïve ways of looking at art I think. Success comes from somewhere else – expressing and connecting with others.

Camille: Is success the goal?

Marika: In your view, is the Estonian art scene diverse enough, is it healthy in the sense that every artistic agent is able to make their voice heard?

Flo: I’m an artist who doesn’t have health insurance – and this is not healthy. Institutions have more power than artists. There could be more artist-run-spaces.

When I was living in Berlin, I felt I could not make it there, there are so many artists in Berlin producing work. It didn’t make sense for me personally to be another artist there. Although in Estonia, we have other problems, in that the scene is so small and therefore gets too comfortable.

Alexei: I think the Estonian art scene is healthy because it’s small. It’s much easier to make things happen on a smaller scale. Everybody knows each other, we have good communication. It’s diverse – many levels of art societies, inter-related art institutions, there’s also underground artists and painters who do flowers or naked women.

Camille: I agree that it is small, but not sure it’s the ideal world. Fortunately, there is less filtering compared to France or Germany – people are more accessible from different scales of institutions or art schools, you can meet them.

On another note, I’m not sure it’s healthy, that the only funding comes from the state, and this can be even dangerous. There’s not enough balance to what the state has to face.

It’s hard for the artist to not be scared to fail. It’s something that can be seen in the art academy. It doesn’t mean that you have to be in a comfortable situation to produce, it’s not a necessity, but facing the fact that there’s no middle class in Estonia, the situation is a bit like swim or drown.

Alexei: Artists coming from abroad, usually are so glad to hear about Kultuurkapital which functions here, because according to my experience, most of the people who apply from there, get support. Even young artists get some amount of money for their first exhibitions in Draakoni or Hobusepea galleries. Compared to Germany for example, where the scene is huge, and is very difficult to sneak into private foundations as there’s is such strong competition.

Camille Laurelli, illustration, "How to: live. Virtual Biographies“, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

Marika: If that was health measured by funding, what about different ideologies?

Alexei: If I look at the report of Kulka, I don’t see that the board is preferring some state agenda. Of course they expect you to have finished higher art school. If you don’t have any education, then you don’t get anything from Kulka.

Bita: Years ago I was very surprised to learn about a list of artists on CCA’s webpage which back then was super short. I noticed that there were no foreign names other than Dénes Farkas who is Estonian-Hungarian. Something even more interesting is that before I moved to Estonia in 2013, I had Finnish friends who lived in Estonia, and they organised a festival called Estomania in Helsinki which exhibited Estonian artists. Those artists I got to know through that festival; the underground art scene of Estonia does not have any connection with the list of artists on the CCA’s website. The artists that I knew from Estonia, are not taken seriously here.

It took me a while to realize that the same problem exists everywhere. There are gatekeepers, institutions, the ones who are in charge of funding, the ones with agency and authority, and they are not necessarily connected to the reality of the art scene. The artists who are validated by them are not necessarily the whole picture. I’m wondering what’s the point of having an official list of artists on the website of the Centre for Contemporary Art. Are these artists and the rest are not?

Bita Razavi, exhibition view „From One Dialectics to Another“ at Valga Museum, 2018

Marika: As I am managing the database, I can explain it a bit. The database doesn’t intend to keep the gates closed but to give an entrance point to the Estonian art scene for foreign art professionals, and also locals. The artists who have their profiles there, is the result of a discussion between several representatives of different art institutions in Estonia, and follows a balance of older generation artists with up-coming artists and their diverse practices. Its goal is not to cover every single artist in Estonia (it’s rather the role of Artists’ Association), but to give information about contemporary artists’ whose presence is strongly felt in Estonia.

Alexei: There’s a funny story, how in 2016 I was exhibiting in Moscow, Evi Pärn was the curator and she made a lecture in the gallery about the Estonian art scene, and she was presenting your website. The first question from the audience was “is it the goal of every artist to get onto that database?”

Camille: Not to say that the database is a good or bad idea – everything depends on context and perspective. For few years I was looking into the Artist Pension Trust (APT) program by mutualart.com and artfacts.net. There were 7 collections in the cooperation and around 2000 artists involved. Every time an artist sold a piece, they divided the income of the sale with the other artists. The goal was to create the biggest contemporary art collection in the world. I was asking myself: if this program wants to become the ultimate artists reference, what about the ones who are not part of this program?

Marika: Is the decision making within art institutions transparent enough? Are there any structures of power that we need to revisit?

Liina: First of all, I am not in that database, but I’m very curious if your life changed after getting there. Second of all, I am one of those, who never got into making applications from Kulka. Writing projects didn’t make sense for me, I felt like the system was against me. I am actually happy to be outside, and not have the need to complain, because that was what the artworld was all the time doing – nonstop complaining – including myself.

Flo: As an artist, I want to do art than to deal with relationships inside and outside of the institutions. Although, if there’s some problem, it’s possible to solve it, because of the small community. Myself personally, I don’t have spare energy to deal with them.

Bita: Flo, what you say, almost makes me cry. Most artists just want to make art, exhibit, and not have to deal with bureaucracy. But not everyone has this privilege. I think that you are coming from a position of power, as you’re well-connected to institutions and don’t need to think much about institutions and structures, because every idea you have is accommodated and realised by institutions. I know that now I am more or less in the same position, but I remember very well the years when I didn’t have any means or possibility to exhibit. And then one day by accident, a friend of mine, Tanel Rander, who I met outside Estonia, invited me to do a show in the tiny town of Valga, and by accident, Anders Härm (curator) passed by and saw my work. Now I am being exhibited in Estonia, but that also may not have happened.

Flo: There are ways to get around not waiting for acceptance. I started my own institution, my house museum. It was a lot of work, though artists should make their own spaces and not wait for curators to invite them in, but do something on their own.

It is bigger challenge to find your place in two countries, and as I mentioned, I couldn’t even dare to think about that challenge in the context of Berlin. In Estonia, it is easy to do something alone, you get visibility quite well – it’s doable.

Flo Kasearu’s house museum, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

Bita: I agree, but it’s not that I was sitting at home, doing nothing, and waiting to be exhibited at Kumu. I was making art all the time and I was part of several artist run spaces. But still when you make your own space, it’s the same story, the space needs visibility, funding, and validation to survive in the long term, which usually comes with the name and visibility of the artists behind it. I made The Yellow House to host other artists, I am running an association called the Post Theatre Collective, together with David Kozma, a platform for artists who are not represented on institutional stages.

Liina: I grew up as an artist in Estonia. For me the whole emphasis goes on making it internationally. More focus was on those who do something abroad. I sensed that they were pushed up. That maybe if the issue is to push the narrative of the hero – then Estonian nationality is a better selling point.

Marika: In relation to this binary inside-outside, I’m thinking of asking Steve. You have a remarkable collection of outsider art, and have worked with prisoners and mentally ill people, although you have a classical education in art. How and what brought you to the “other” side? What kind of benefits does it bring, in comparison to the ones who are “inside”?

Steve: I was very fortunate as I had one professor, Phil Hitchcock, during university, who opened me up to some great outsider art work. Some 30 miles away from Sacramento, where I lived for most of my life, Martín Ramirez had been institutionalised in DeWitt State Hospital for 15 years. He is one of my favourite artists; one of the greatest artists who ever lived – outside or not outside.

Through my working with mentally disabled people for 18 years, I learned more about the outsider art world. It exploded in the mid 90s in the US. There was a lot great work being done by outsider artists with no knowledge of art, art history, galleries, or the contemporary art scene, but for some reason they were creating work outside the artworld. Outsider art goes back to 1920s when Hans Prinzhorn published “Artistry of the Mentally Ill”, which had a huge influence on modern art.

Some of the most powerful art in the world is outsider art and the people who see it, wish that they could unlearn their education to make this beautiful, raw artwork. The narrative of the creator and their history is secondary, and can either help to enrich or detract from what you are experiencing. Whether the work is created by an academically trained artist or not is of little consequence upon the initial viewing of the work for me.

Bita: The group of artists that I knew as Estonian artists before moving to Estonia – Steve was one of them. But now I don’t see them active anymore.

Steve: They are still around, but they are a little shy. They keep it to themselves.

Marika: How about relations within the Estonian art scene – are there outside-inside discourses?

Bita: It came to my mind that there is also the issue of being from Tallinn or outside-Tallinn. For a very long time I had conversations with Diana Tamane (a Latvian-born artist working mainly in Tartu) who is surprisingly absent from this discussion. We always shared the feeling of not being able to penetrate the Estonian art system and exhibit in Tallinn.

Alexei: There are different art scenes in Tallinn and Tartu. The ones who have a studio in Tartu, also exhibit in Tartu.

Bita: Maybe that’s the problem, the Tartu art scene not necessarily being connected to the Tallinn art scene, and at the end of the day, as Liina mentioned, successful artists seem to be the ones who are exported and internationally exhibited.

Camille: When I arrived here in 2015, I already had connections with Estonia, through coming for exhibitions or workshops. I became quickly involved with the art scene. When I was in France, initiatives took ages, because everything is so bureaucratic, with many administrations to pass through and intermediators to meet. Maybe I was lucky to meet the right people at the right time, but I’ve always had support for anything I wanted to launch. It was with people I actually didn’t expect to get support, because I didn’t know them.

Alexei: When I was younger, I did some guerrilla exhibiting after graduating. I didn’t even try to get into official scene; I was just doing my stuff and exhibiting in some half-abandoned place, rented with symbolic money. Step-by-step people started to notice it. After graduating it took 7-8 years to get at least some recognition, before I was never in the official gallery scene – Hobusepea, Draakoni. It’s good not to get into the scene directly after graduating, you have to search, experience some poverty, loss of hope, not believing in the future. It’s okay to have 6-7 years of being nobody. Just do your art, it makes you stronger.

Steve Vanoni’s studio, Pärnu Creative District, 2021. Photo: Ago Tammik, Ekspress Meedia

Marika: How has moving from one country to another affected your artistic practice?

Camille: Everything I’m doing is part of my practice, with my interest in art. My art constantly, accidentally, or intentionally correlates with my life.

Liina: I’ve focused on the Estonian-language content. I am making work for Estonians. This only happens because I don’t live in Estonia: it is informed by my experience of living abroad in several ways. It has to do with home-sickness, and that my mum doesn’t understand what I do. Here it is somehow easier to express myself in my own language. If I say some things in Estonian, it seems somehow more real. I found a middle-ground for not living in Estonia but working for Estonia.

Bita: I’ve moved too many times to have a sense of where is originally home. I don’t have a memory of moving being a major obstacle. Although I encountered some big contrasts when moving to Helsinki in my early twenties. I took this outsider’s perspective or observation as material for making art, and it became the core of my work. I think when you move to a new society or space you notice things that the locals are blind to.

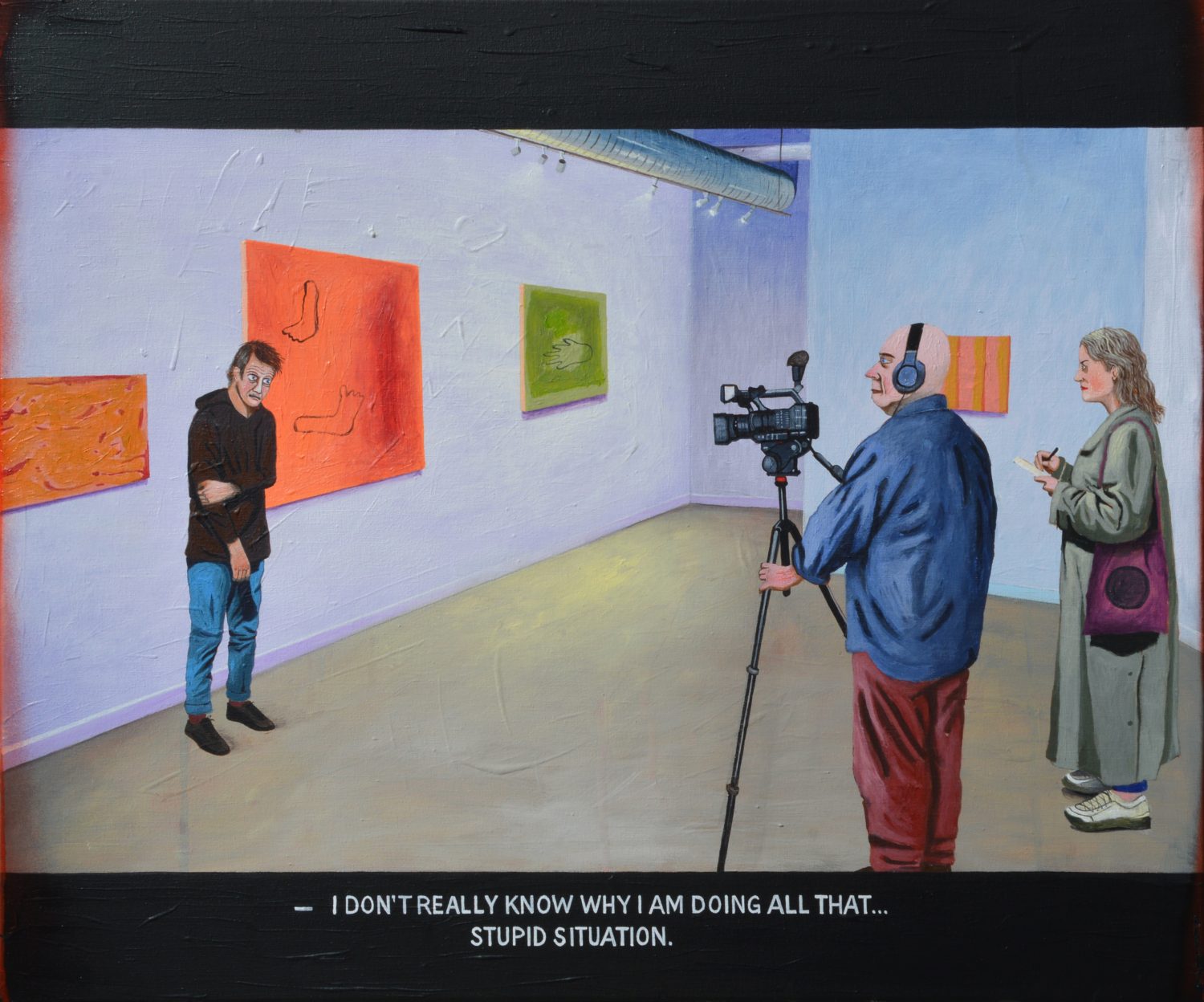

Alexei Gordin, Interview. 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Marika: Having one of the artists, Alexei, at the discussion, whose work represents almost an absurd yet painfully honest joke on the art world, I’d like to ask how much do you draw from the reality? Is the situation as bad as in your paintings?

Alexei: No, I’m just trying to underline some things, which have happened with me, but my work has an ironic layer. What I’m showing is not 100% true, although there is collective consent of what is happening. This language of meme which I’m using – I like it – a simple picture and two words – everyone can relate to. It is exaggerated version of reality. Often a caricature depicts the character more precisely than a realistic portrait.

Alexei Gordin began exhibiting at the beginning of the 2010s. Using black humour, Gordin draws attention to the absurdity of the (art) world and alienation, highlighting issues like inequality and the difficulties of marginalised groups.

Camille Laurelli’s work is often confusing, misleading, based on failure, pirated and provoked misunderstandings, hence it often leaves the art field, and even his mother, confused.

Flo Kasearu often uses biographical material as the basis for her works. In 2013 she founded a house museum, a site specific and continuously developing thematic exposition of the artist’s work in her own home.

Bita Razavi is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice is centered around observations on everyday situations and bringing the personal to the public sphere.

Steve Vanoni is an artist from California, USA. He has managed a gallery and art community Horse Cow. He has thouroughly dealt with outsider art, collected it and shown it in Viljandi Kondas Centre (2016).

Liina Pääsuke is a podcaster with contemporary art background. She is the second person from Väätsa (small village in the middle of Estonia), who has graduated Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Since 2019 she runs „liina’s show“ in kolkaplika radio and keeps crypto besides the i-s in her name.

This text is part of a collaboration between EDIT and Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art’s web magazine. In every two months EDIT will publish a text about Estonian art and the CCA magazine will publish an article about Finnish art scene. This article swap aims to keep up cultural exchange and awareness of the art scenes of neighbouring countries during the time when travelling and direct communication is complicated.

Moderated and written by Marika Agu.

Text has been language-edited by Paul Emmet.

Main image: Participants of the discussion in CCA Office. From the left: Steve Vanoni, Marika Agu, Camille Laurelli, Alexei Gordin, Bita Razavi and in the back Flo Kasearu, Liina Pääsuke, 2021 (cropped)