Race and wages: Listening to the debates in Estonia

19.5.2021

Sulje

Sulje

19.5.2021

The new permanent exhibition Landscapes of Identity: Estonian Art 1700–1945 in Kumu Art Museum brings up new questions about the management of museums, galleries, and art collections, when rephrasing artworks with racist titles. In Estonia, also the discussion around wages for artists and other freelancers has been heated up again, write Marika Agu and Kaarin Kivirähk from the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art.

Did you know that the Collar of the Order of the National Coat of Arms of the first Estonian President, Konstantin Päts, is still kept in Moscow? Made by artist Paul Luhtein in 1936, this three centimetre thick gold chain decorated with a ruby, three sapphires and 94 diamonds has been requested to be returned to Estonia several times, with no success.

While Germany is returning the Benin bronze sculptures to Nigeria, as one example of current processes of revisiting colonial history and recuperating from its effects, the Art Museum of Estonia has also taken steps in overseeing its collections in such regard. Usually colonialism and racism are addressed in Estonia from the point of the victim, as is the story with the collar of the order of President Päts previously mentioned. Nevertheless, the new permanent exhibition Landscapes of Identity: Estonian Art 1700–1945 (curators Linda Kaljundi and Kadi Polli) in Kumu Art Museum approached the topic from a different angle. Here, the main discussion is presented in the exhibition space entitled Rendering Race, which rephrased artworks with racist titles. Although, being a standard procedure among artworks and artefacts dating from centuries ago and which lack information, the precedence, introduced by the curator Bart Pushaw, provoked an immediate controversy amongst the Estonian general public.

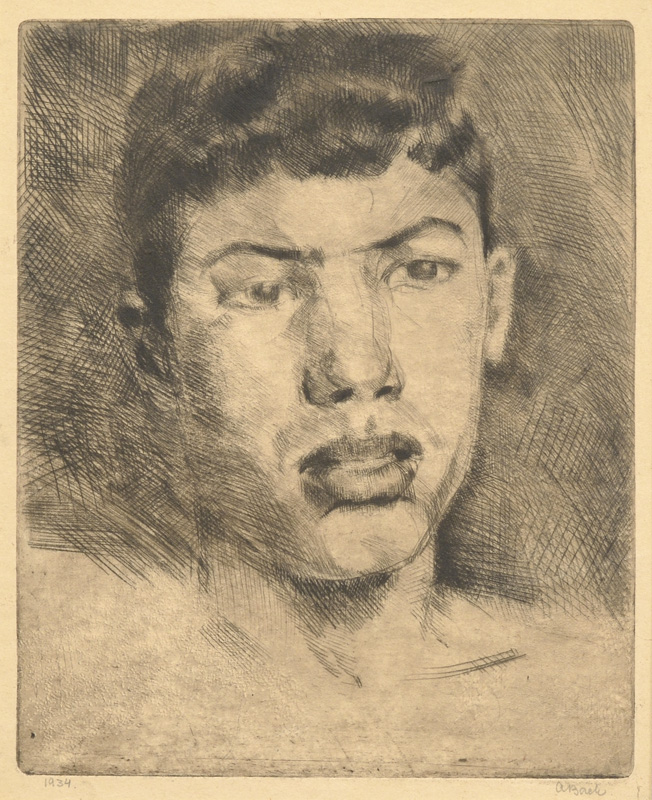

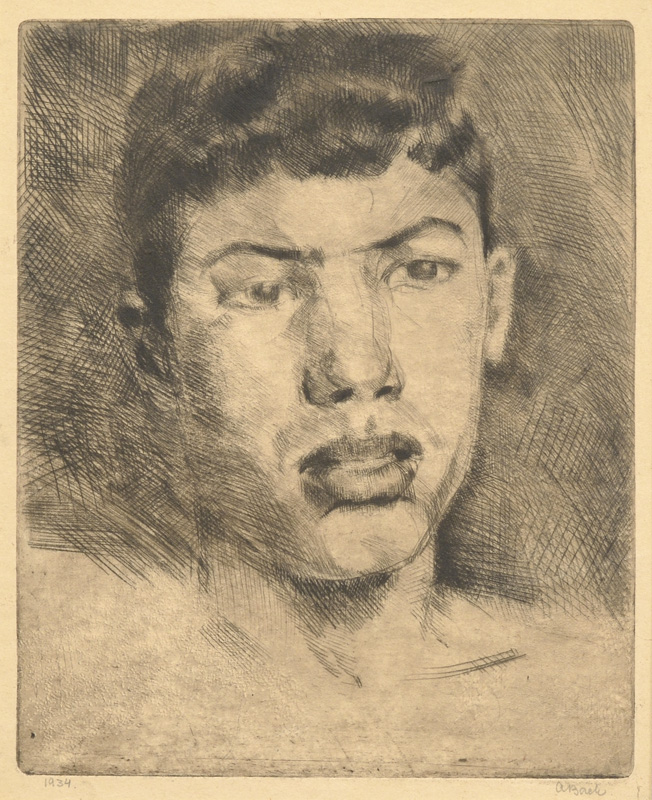

In several cases, the artworks were not titled by the authors, but instead by the historical keeper of the collection. Hence, the corresponding titles required updating to meet the standards of the present. Indeed, what the curator did was to suggest less race distinguished titles, as for instance, Seated Woman instead of Seated Mulatto (pencil drawing by Eduard Wiiralt) or Young Roma instead of Young Gypsy (etching by Aino Bach), and the like. Interesting new facts have also appeared in the process of revisiting artworks from the early 20th century. For example, Pushaw describes in an interview, a person on Wiiralt’s artwork Heads as been identified as a Cuban artist instead of an anonymous model. This leads to new possible research trajectories, as for instance, what were the relationships between Estonian and Cuban artists in the past? And who decides on the correctness of art etiquette?

The new exhibition shows that early Estonian art was in dialogue with the art of other regions, and also brings up new questions about the management of museums, galleries, and art collections. Estonia has the highest number of museums per person in the European Union, and considerable resources are allocated to their up-keep. Currently the second biggest art collection based in Tartu Art Museum is waiting for financial support to build a new building in the heart of Tartu, shared with the city library. Since its founding in 1940, Tartu Art Museum has been housed in temporary spaces which are not designed for exhibition and preservation purposes, and therefore discussions for an specially built building have always existed. The debates accompanied with the petitions are heated, some prefer to maintain the depreciated park, where the new building is planned, some say what Tartu needs is not a place to visit well-produced exhibitions, but a place for imagining new ways of art making.

Of course, one might ask if the Estonian art scene really needs another building when the artist fees are still very small, and professionals are competing with each other for crumbs. The discussions around wages for artists and other freelancers are getting bigger every now and then, sometimes also resulting in important changes. Now the discussion has been heated up again, partly because of the health crisis which made the state of freelancers even more precarious than before. In a short survey for artists CCA conducted last year, most of the people who answered the questionnaire had lost more than half of their income because of the pandemic. But as a lot of artists have brought out – the Covid-19 situation is only the tip of the iceberg.

Artists living in constant crisis and precarity is, indeed, nothing new. But this is not an excuse however for not improving the material conditions of artists. Art institutions (CCA together with Artists Union and the Estonian Contemporary Art Development Centre) have started to put together a development plan for the next five years for the Estonian art field, which should be used as a tool by art institutions and activists to make structural changes in the field. The Estonian Ministry of Culture is conducting a big-scale survey on the state of freelancers at the moment. Art workers Airi Triisberg and Maarin Ektermann are mapping the existing wages of artists (and other art workers, including art writers, as their fees have also been incredibly low as far as anyone remembers), and proposing new possible standard fees that would be based at least on the minimum wage in Estonia (584 euros a month, gross), or the minimum wage of cultural workers which is applied in state funded institutions (1300 euros).

This would also be the minimum, which, together with social tax paid from this sum, would provide the social security for a person. As Triisberg expressed in an interview, this step would solve the massive problem of freelancers not having social security. However, in practical terms, this seemingly small step is hard to achieve as art institutions mostly work based on (decreasing) public funding. Today, even if big institutions would start calculating the artist fee based on the national minimum wage, the budgets of those institutions would increase massively. So, the big question remains: How to work with existing budgets while trying to create sustainable working conditions for everyone, but at the same time creating meaningful content, well-produced exhibitions and attractive communication? Is it even possible, and if not, what are the aspects we are ready to give up if needed?

Illustration by Kadi Estland for CCA magazine on the topic of artists wages. The text says - The artists came and brought food, and said they will even work for free.

Rendering race. Project space exhibition curated by Bart Pushaw at the new permanent exhibition in Kumu art museum, Tallinn. Photo by Stanislav Stepaško

This text is part of a collaboration between EDIT and Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art’s web magazine. In every two months EDIT will publish a text about Estonian art and the CCA magazine will publish an article about Finnish art scene. This article swap aims to keep up cultural exchange and awareness of the art scenes of neighbouring countries during the time when travelling and direct communication is complicated.

Text: Marika Agu and Kaarin Kivirähk

Main image: Aino Bach: Young Roma (1934) | Estonian Art Museum collection